|

In contrast to micelles and bilayers, which are composed of aggregates of single and double chain amphphiles,

proteins are covalent polymers of 20 different amino acids, which fold, to a first approximation, in a thermodynamically

spontaneous process into a single unique conformation, theoretically at a global energy minimum. This section will investigate

the possible conformations available to proteins, just as we studied the conformations of free fatty acids and acyl chains

in lipid aggregates. The next section will discuss the actual processes of folding and of unfolding (denaturation), both in

vitro and in vivo. The last will discuss the thermodynamics and intermolecular forces which stabilize

the folded (or native) shape and the unfolded (or denatured state) of proteins, in a fashion similar to how we discussed micelle

and bilayer stability.

Main Chain Conformations - Cis/Trans Peptide Bonds/ Ramachandran Plots

Just as saturated fatty acid chains have preferred conformations (all ttt), peptide chains

also have preferred conformations. The complexity is much greater, however. With fatty acid chains, we dealt only with torsion

or dihedral angles around the methylene carbons. For proteins, we must consider the covalent links which attach the amino

acids together, as well as the rotations possible in 20 different amino acids. The peptide bonds connects the carbonyl C of

the ith amino acid to the alpha amine N of the ith+1 amino acid. The resulting bond is an amide link.

X-ray analysis shows that the the C-N bond has double bond character. This can be accounted for by delocalizing the nonbonding

electron pair of the N to the carbonyl C forming a double bond, with the pi bonded electrons of the carbonyl C-O bond moving

to the O. These resonance structures literally force the two other atoms connected to the carbonyl C and the amide N to lie

in a plane, since the hybridization of the C and N are sp2, with 120o bond angles. This greatly simplifies

the number of conformations which a protein can adopt since these 6 atoms are forced to reside and move in a plane. The alpha

C serves as the corner attachment point of two different planes, each which can rotate independently of the other plane.

The two planes can twist around the alpha carbon. The rotation angles for the two planes are called phi and psi.

Phi and psi are analogous to the torsion angles in the acyl chains of fatty acid. They can vary from -180 to +180o.

The R group substituent attached to the alpha C can also rotate around the alpha C and the beta C of the side chain.

This angle is defined as chi.. Other rotations also occur within the side chain. We will concentrate on the phi

and psi in this section.

Figure: Extended Polypeptide Showing Planes

and Phi/Psi Angles

Another important feature of the peptide bond is that the alpha Cs at opposite ends of the

rectangle are usually trans to each other (on opposite sides of the C-N bond in the peptide bond. This trans arrangement of the alpha C's is sterically favored by a factor of 1000/1 for all peptide bonds except X-Pro. Pro, which is a cyclic amino acid,

is sterically restricted. The link above, which also shows the X-Pro bond, clearly shows that both the trans and cis

forms of the X-Pro bonds are hindered to a similar extent. In X-Pro bonds in proteins, the trans/cis ratio found in proteins

is 4/1. The diagram shows a trans dipeptide, and how this can be converted to cis through rotation around the C-N bond.

A protein can now be thought of as a series of linked sequences of rigid, planar peptide units which

can rotate around phi-psi angles. When the chain is fully extended (as shown in the links above), phi and psi are 180o.

When they equal 0o, the two peptide bonds flanking the alpha C are in the same plane. This

conformation is prohibited since the O of the C=O on one plane and the H of the H-N on the other are overlapping - i.e. they

approach closer than their van der Waals radii.

This simple example shows that all conformational space is not accessible.

A Web Tutorial - Phi/Psi Angles Requires SGI - Cosmo Player . This is an , interactive tutorial

that displays two planes connected to an alpha carbon. You can rotate each plane independently, and pick any phi/psi

angle and see what the planes look like.

Ramachandran was the first to calculate which phi-psi angles are allowed. He modeled the angles permitted

to a tripeptide, assuming the atoms were hard spheres. The angles allowed depended in part on the limiting distance chosen

for interatomic contacts. (i.e. the usual H -- H distance is 2.0 angstroms, and 3.0 for C--C bonds.) The plot below

show the allowed regions in red. Only 3 small regions of conformational space are available. If you allow

a closer approach by 0.1 angstrom, more conformation space is available, but only one new area is available (shown in yellow

in the plot below).

Figure: Ramachandran plot

A Ramachandran plot of Ala-Ala-Ala is nearly identical to the plot for Phe-Phe-Phe (which is unbranched

at the beta carbon (the first methylene C in the side chain). The plot for Thr-Thr-Thr, which has a branch at the beta C (with

OH and CH3 attached) shows somewhat less room than the other plots. Pro-Pro-Pro is most restricted for obvious

reasons. For a longer chain than a tripeptide, there are more restrictions than for (Ala)3, since the chain can't

assume a conformation when it passes through itself. The plots for actual proteins have many points which do fall in forbidden

regions. However, these points would be allowed if the peptide bonds is twisted a few degrees. Gly bonds also fall outside

the allowed regions. This is understandable, since the side chain of Gly is H, and it is used in protein where sharp turns

of the chain is necessary. Right hand alpha helices fall at -57,-47 while left hand alpha helices fall at +57,+47. (Notice

these are not mirror images of each other. The mirror image of a right-handed alpha helix would be a left handed helix made

of D-amino acids.) Parallel beta sheets are at -119, -113, while antiparallel sheets falls at -139, +135. Other types of helices

also are found. The 310 helix , a sharper helix with 3 amino acids/turn, falls at -49,-26. All of these examples

of secondary structure fall in allowed regions. Modern Ramachandran plots do not model the atoms as hard spheres but instead

consider the potential energy of the atoms using the Lennard-Jones potential (6-12 potential) for van der Waals interactions. We discussed this potential function in the molecular modeling lab.

Figure: Ramachandran plots showing Phi, Psi angles for Gly, Ala, Tyr, and Pro in actual proteins

Secondary Structure

Secondary structures are those repetitive structures involving H bond between amide H and carbonyl O in-

the main chain. These include alpha helices, beta strands (sheets) and reverse turns..

Alpha Structure

Figure: Right Handed Alpha helices -

These helices are formed when the carbonyl O of the ith amino acid H bonds to the amide H of

the ith +3 aa (or from the first to fourth amino acids). The phi-psi angles for those amino acids in the

alpha helix are - 57,-47, which emphasizes the regular repeating nature of the structure. It can also be characterized by

n (the number of peptide units/turn = 3.6) and pitch (the helix rise/turn = 5.4 angstroms). Some facts:

- the alpha helix is more compact than the fully extended polypeptide chain with phi/psi angles of 180o

- in proteins, the average number of amino acids in a helix is 11, which gives 3 turns.

- the left-handed alpha helix, although allowed from inspections of a Ramachandran plot, is never observed,

since the side chains are too close to the backbone.

- the core of the helix is packed tightly. There are not holes or pores in the helix.

- All the R-groups extend backward and away from the helix axis.

- Some amino acids are more commonly found in alpha helices than other. Amino acids can be divided into

two kinds, those with branches at the beta C and those with none. Consider first those that aren't branched . Gly is too conformationally

flexible to be found with high frequency in alpha helices, while Pro is too rigid. The amino acids with side chains that can

H-bond (Ser, Asp, and Asn) and aren't too long appear to act as competitors of main chain H bond donor and acceptors, and

destabilize alpha helices. The rest with no branches at the beta C can form helices. Those with branches at the beta carbon

(Val, Ile) destabilize the alpha helix due to steric interactions of the bulky side chains with the helix backbone. (Remember

left-handed alpha helices are not found in nature for similar reasons.) Summary of amino acids propensities for alpha helices (and beta structure as well)

- alpha keratins, the major component of hair, skin, fur, beaks, and fingernails, are almost all alpha

helix.

Note: There are other kinds

of helices that can occur. These include a 310 helix and a p

helix, which are stabilized by H-bonds between the amide NH and carbonyl O of residues (i, i+2) and

(i, i=4), respectively. Likewise, they have 3 and 4.3 residues/turn, respectively, and a rise per residue of 6 and 4.7

angstrom, respectively. These structures are much rarer than right handed alpha helices.

| Helix Type |

H bond btw ith and ith+X AA, where X = |

Residue/turn |

Rise (Angstrom)/turn |

| 310 |

2 |

3 |

6 |

| a |

3 |

3.6 |

5.4 |

| p |

4 |

4.3 |

4.7 |

Beta Structure

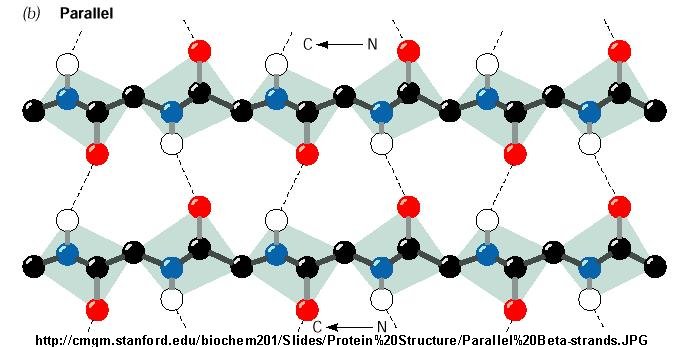

Figure: Parallel Beta Strands

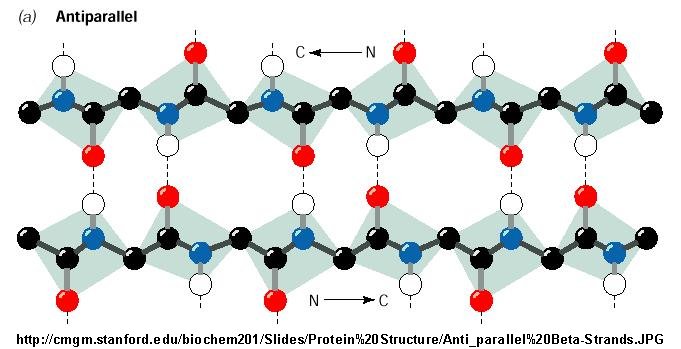

Figure: Antiparallel Beta Strand

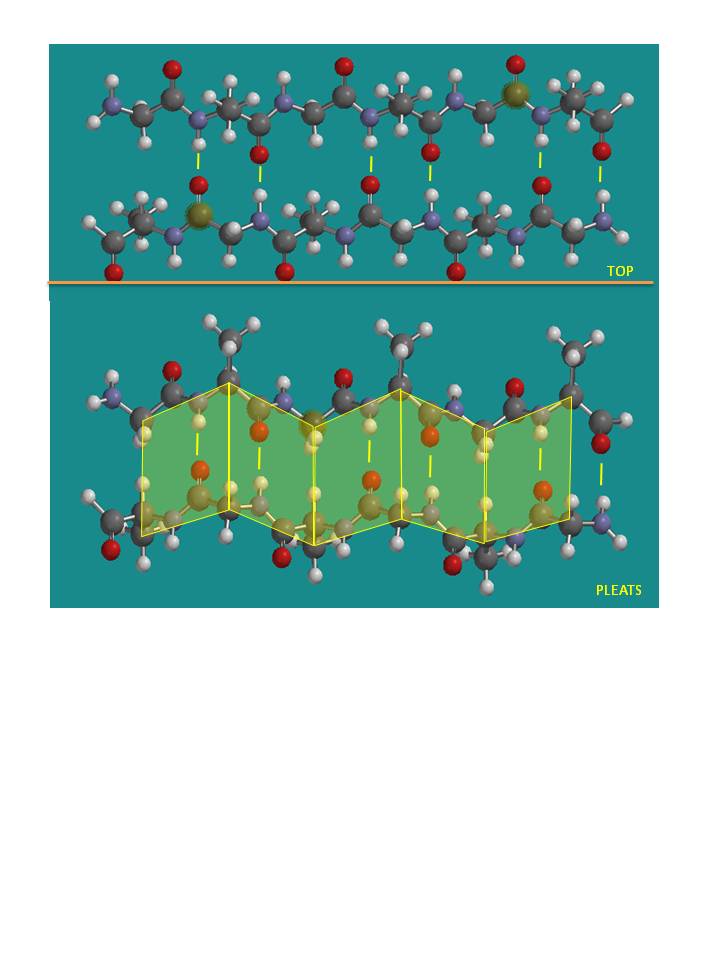

Beta Structure: Parallel and antiparallel beta strands are much more extended than alpha helices

(phi/psi of -57,-47) but not as extended as a fully extended polypeptide chain (with phi-psi angles of +/- 180). The beta

sheets are not quit so extended (parallel -119, +113 ; antiparallel, -139, +135), and can be envisioned as rippled sheets.

They can be visualized by laying thin, pleated strips of paper side by side to make a "pleated sheet" of paper. Each strip

of paper can be pictured as a single peptide strand in which the peptide backbone makes a zig-zag along the strip, with the

alpha carbons lying at the folds of the pleats. Each single strand of the beta-sheet can be pictured as a twofold helix, i.e.

a helix with 2 residues/turn. The arrangement of each successive peptide plane is pleated due to the tetrahedral nature of

the alpha C. The H bonds are interstrand, not intrastrand as in the alpha helix.

Figure: Antiparallel pleated beta sheet

Note: Consider a strand as a continuous and contiguous polypeptide backbone propagating

in one direction. Hence, using this definition, a helix consist of a single strand, and all the H-bonds are within the strand

(or intrastrand). A beta sheet would then consist of multiple strands, since each "strand" is separated from other "strands"

by an intervening contiguous stretch of amino acid which bends within the protein in a way which allows the next section of

the peptide backbone, the next "strand" to H-bond with the first "strand". But remember, even in this case, all the H-bonds

holding the alpha and beta structure together are intramolecular.

In a parallel beta sheet structure, the optimal H bond pattern leads to a less extended structure (phi,

psi of -119, +113) than the optimal arrangement of the H bonds in the antiparallel structure (phi, psi of -139, +135). Also

the H bonds in the parallel sheet are bent significantly. (i.e. the carbonyl O on one strand is not exactly opposite the amide

H on the adjacent strand, as it is in the antiparallel sheet.) Hence antiparallel

beta strands are presumably more stable, even though both are abundantly found in nature. Short parallel beta sheets

of 4 strands or less are not common, which might reflect their lower stability. .

The side chains in the beta sheet are normal to the plane of the sheet, extending out from the plane on

alternating sides. Parallel sheets characteristically distribute hydrophobic side chains on both side of the sheet,

while antiparallel sheets are usually arranged with all the hydrophobic residues on one side. This requires an alternation

of hydrophilic and hydrophobic side chains in the primary sequence. Antiparallel sheets are found in silk with the sheets

running parallel to the silk fibers. The following repeat is found in the primary sequence: (Ser-Gly-Ala-Gly)n),

with Gly pointing out from one face, and Ser or Ala from the other.

Beta strands have a tendency to twist in the right hand direction. This leads to important

consequences in how the beta strands are connected. Parallel strands can from twisted sheets or saddles as well as beta barrels.

Figure: twisted sheets or saddles as well as beta barrels

- in parallel strands, right handed connectivity is common.

- in a protein with parallel strand in register, and given the inherent twist in the stands, the strands

arrange in a way to have the H bonds stretched equally at the ends of the chains, giving rise to a twisted saddle shape (top

structure above).

- in a protein with parallel strand out of register, and given the inherent twist in the stands,

the strands arrange in a way to have the H bonds stretched equally at the ends of the chains, giving rise to a beta barrel

(bottom structure above).

Reverse Turns: About 50% of the amino

acids in a globular protein are in regular secondary structure (alpha or beta). The remaining amino acids are not less ordered,

just less regular. An additional example of secondary structures is reverse turns (or beta-bends or beta turns). Reverse turns

often connect successive antiparallel beta strands and are then called beta hairpins.

Figure: Reverse Turns

They are almost always at the surface, and consist of 4 amino acids. There are two types. (I - phi2 =

-60, psi2=-30; phi3 = -90, psi3 = 0; II - phi2 = -60, psi2=120; phi3 = 90, psi3 = 0 ) Residue 2 of both is often Pro. (Why?)

Both have an H bond between the carbonyl O of the ith a.a and the amide H of the ith+3 aa (as in the

alpha-helix). In the type 2, the O of residue 2 crowds the beta C of residue 3, so aa2 is usually Gly. Why? Those amino

acids which destabilize alpha helices are often found in beta sheets, since the side chains project out of the plan which

holds the main chain.

Figure: Type I and Type II Reverse Turns

-

Chime Molecule Modeling; This reverse turn structure consists of amino acids 20-26 from Trypsin Inhibitor 2 from Eballium elaterium. Notice the tightness of the reverse

turn and the presence of Pro and Gly. (Use Chime mouse controls to alter rendering.)

-

Chime Molecule Modeling: Another view of the reverse turn from intestinal fatty acid binding protein. (Use Chime mouse controls

to alter rendering. First go to Select, Mouse Control, then select center of rotation.)

Figure: Why do amino acid propensities for secondary structure differ?

3o Structure

The tertiary structure of a protein is its 3D structure. From the crystal structure of thousands

of proteins, common features of protein structure is observed: (Recent Data: new values shown in red.

based on much crystallographic data; added 9/26/02 based on paper: Pace, C.N. Biochemistry. 40, pg 310 (2001))

- On average, about 50% of the amino acids are in secondary structure. On average, there is about 27% alpha

helix, and 23% beta structure. Of course, some proteins are all alpha-helical, and some are all beta structure, but most are

a mixture.

- The side chain location varies with polarity. Nonpolar side chains, such as Val, Leu, Ile, Met, and Phe

are nearly always (83%) in the interior of the protein.

- Charged polar side chains are almost invariably on the surface of the protein. (54%

- Asp, Glu, His, Arg, Lys are buried away from water, a bit startling)

- Uncharged polar groups such as Ser, Thr, Asn, Gln, Tyr, and Trp are usually on the surface, but frequently

in the interior. If they are inside, they are almost always H bonded (63% buried - Asn, Gln, Ser, Thr,

Tyr) .

- Globular proteins are quite compact, with water excluded. The packing density (Vvdw/Vtot)

is about 0.75, which is like the NaCl crystal and equals the closest packing density of 0.74. This compares to organic liquids,

whose density is about 0.6-0.7.

Common Motifs Found in Proteins

Super-Secondary Structure - Given the number of possible

combinations of 1o, 2o, and 3o structures, one might guess that the 3D structure of each

protein is quite distinctive. This is true. However, it has been found that similar substructures are found in proteins. For

instance, common secondary structures are often grouped together to form a motif called super-secondary structure (SSS). See

the example below:

- helix-loop-helix : found in DNA binding proteins

and also in calcium binding proteins. This motif, which is also a helix-loop-helix, is often called the EF

hand. The loop region in calcium binding proteins are enriched in Asp, Glu, Ser,

and Thr. Why?

Figure: helix-loop-helix

Figure: EF Hand

- beta-hairpin or beta-beta: is present in most antiparallel beta structures

both as an isolated ribbon and as part of beta sheets.

Figure: beta-hairpin, or beta-beta

- Greek Key motif: four adjacent antiparallel beta strands are often arranged in a pattern similar to the repeating

unit of one of the ornamental patterns used in ancient Greece.

Figure: Greek Key Motiff

- Figure: beta-alpha-beta: is a common way to connect two

parallel beta strands. (beta hairpin used for antiparallel beta strands).

Figure: beta-alpha-beta

-

Beta Helices: These right-handed parallel helix structures consists of a contiguous polypeptide chain with three parallel beta strands

separated by three turns forming a single rung of a larger helical structure which in total might contain as many as nine

rungs. The intrastrand H-bonds are between parallel beta strands in separate rungs. These seem to prevalent in

pathogens (bacteria, viruses, toxins) proteins that facilitate binding of the pathogen to a host cell.

|

Vibrio cholerae |

cholera

|

|

Helicobacter pylori |

ulcers |

|

Plasmodium falciparum |

malaria |

|

Chlamyidia trachomatis |

VD |

|

Chlamydophilia pneumoniae |

respiratory infection |

|

Trypanosoma brucei |

sleeping sickness |

|

Borrelia burgdorferi |

Lymes disease |

|

Bordetella parapertussis |

whooping cough |

|

Bacillus anthracis |

anthrax |

|

Neisseria meningitides |

menigitis |

|

Legionaella pneumophilia |

Legionaire’s disease |

Domains - Domains are the fundamental unit of 3o structure.

It can be considered a chain or part of a chain that can independently fold into a stable tertiary structure. Domains are

units of structure but can also be units of function. Some proteins can be cleaved at a single peptide bonds to form two fragments.

Often, these can fold independently of each other, and sometimes each unit retains an activity that was present in the uncleaved

protein. Sometimes binding sites on the proteins are found in the interface between the structural domains. Many proteins

seem to share functional and structure domains, suggesting that the DNA of each shared domain might have arisen from duplication

of a primordial gene with a particular structure and function.

Evolution has led towards increasing complexity which has required proteins of new structure and function.

Increased and different functionalities in proteins have been obtained with additions of domains to base protein. Chothia

(2003) has defined domain in an evolutionary sense as "an evolutionary unit whose coding sequence can be duplicated and/or

undergo recombination". Proteins range from small with a single domain (typically from 100-250 amino acids) to large

with many domains. From recent analyzes of genomes, new protein functionalities appear to arise from addition or exchange

of other domains which, according to Chothia, result from

- "duplication of sequences that code for one or more domains

- divergence of duplicated sequences by mutations, deletions, and insertions that produce modified structures

that may have useful new properties to be selected

- recombination of genes that result in novel arrangement of domains."

Structural analyses show that about half of all protein coding sequences in genomes are homologous to

other known protein structures. There appears to be about 750 different families of domains (i.e small proteins derived

from a common ancestor) in vertebrates, each with about 50 homologous structures. About 430 of these domain families

are found in all the genomes that have been solved.

Structual Clases of Proteins - Proteins can be divided into 3 classes

of protein, depending on their characteristic secondary structure. Click below for Chime structures showing examples of these

proteins.

- alpha proteins - consist of predominately alpha helix.

- alpha/beta proteins - consist of a common of alpha and beta structure. These are the

most common class.

- beta proteins - consist of predominantly beta structure.

Quarternary Structure

Primary structure is the linear sequence of the protein. Secondary structure is the repetitive

structure formed from H-bonds among backbone amide H and carbonyl O atoms. Tertiary structure is the overall 3D structure

of the protein. Quaternary structure is the overall structure that arises when tertiary structures aggregate to self

to form homodimers, homotrimers, or homopolymers OR aggregate with different proteins to form heteropolymers.

Globular versus fibril structures

We will deal exclusively with proteins which have a "globular" tertiary structure in this course.

However, there are many proteins that form elongated fibrils with properties like elasticity, which measures the extent

of deformation with a given force and subsequent return to the original state. Elastic molecules must store energy (go

to a higher energy state) when the elongating force is applied, and the energy must be released on return to the equilibrium

resting structure. Structures that can store energy and release it when subjected to a force have resiliency.

Proteins that stretch with an applied forces include elastin (in blood vessels, lungs and skins where elasticity is

required), resilin in insects (which stretches on wing beating), silk, found in spider web) and fibrillin

found in most connective tissues and cartilage. Some proteins have high resiliency (90% in elastin and resilin), while

others are only partially resilient (35% in silk, which have a tensile strength approaching that of stainless steel.

In contrast to rubber, which has an amorphous structure which imparts elasticity, these proteins, although they have a dissimilar

amino acid sequence, seem to have a common structure inferred from their DNA sequences. In some (like fibrillin), the

protein has a folded b-sheet domain which unfold like a stretched accordion.

Others (like elastin and spider silk) have b-sheet domain and other

secondary structures (a-helices and (b turns) along with Pro and Ala repetitions. Researcher are studying these structures to help in the synthesis

of new elastic and resilient products

|